Some (most) elements will not work without it!

The Arnhem Fighter Control Story

A Briefing Paper

by

The Association of RAF Fighter Control Officers

Acknowledgment

This paper has been compiled from a number of sources. Squadron Leader Mike Dean generously provided information and advice. The Association also acknowledges information it gathered from a paper by FR Hunt entitled Glider-Borne Radar and an article by Squadron Leader Frank Hayward which was published in Air Clues in the Winter of 1994. Some facts have been taken from Government sources and under the terms of the standard Open Government Licence we would like to acknowledge the importance of Air Publications 1063, 3237 and 1116 which were produced by the Air Historical Branch in the 1950s

Fighter Control During Operation Market Garden

Introduction

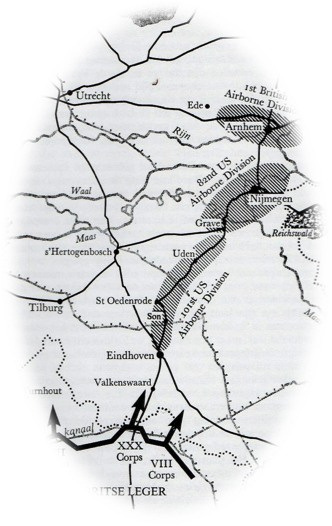

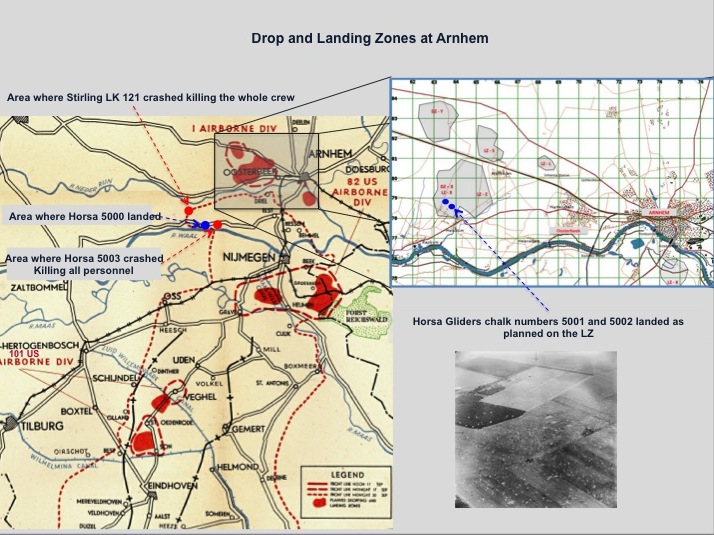

Figure 2 - The Market Garden Plan

On the 16th September 1944 Wing Commander Laurance Brown, arguably the first Fighter Control Ace with over 100 kills to his name, met with General 'Boy' Browning to persuade him to include mobile radar units as part of the air landing at Arnhem. He won the day but little did he know that in doing so he was the architect of his own death.

Figure 1 - The bridge at Arnhem

As the Allies advanced into Holland they faced increasingly fierce resistance and to advance into Germany itself they were faced with some significant challenges in the guise of a number of difficult river crossings culminating with a need to cross the Rhine (Neder Rijn) and a defensive barrier called the Siegfried Line. Additionally, the British Second Army advance lost momentum because of the difficulty in resupplying it from Normandy.

Field Marshal Montgomery devised a plan to reinvigorate the British advance, capture important bridges crossings the Maas at Grave, the Waal at Nijmegen and the Neder Rijn at Arnhem. The bridge at Arnhem was particularly important because the Neder Rijn was over 100 metres wide at this point.

Put simply, the plan was to capture the bridges through vertical envelopment which would essentially create a corridor for the rapid advance of a main, Corps-sized, field force. This entailed three parachute Divisions, one British and two American, being dropped with supporting echelons to capture the bridges and the British XXX Corps advancing rapidly North to consolidate the capture of the bridges and to position for a flanking attack into Germany. The British XXX Corps had to advance some 70 miles to reach Arnhem along a single road axis. The operation was code named Market Garden with Operation Market covering the airborne assault and Operation Garden for the advance of XXX Corps.

Radar Coverage

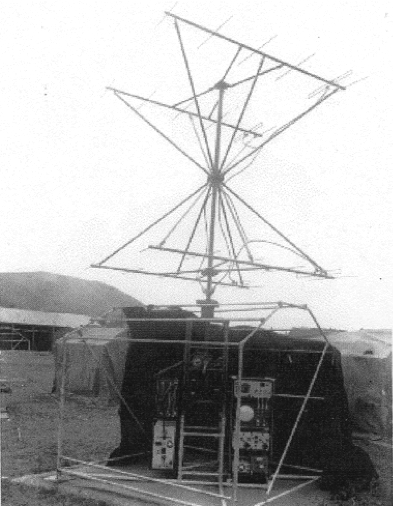

Figure 3 - A Light Warning Set in a Tent

Radar surveillance and control coverage of the pocket at Arnhem was not good enough to provide effective fighter protection for the troops on the ground because all the Fighter Direction Posts (FDP) and Ground Control Interception (GCI) units were behind the main front line in some cases by several miles. Lieutenant General Lewis H Brereton, Commanding General of the Allied Airborne Army articulated on the 18th August 1944 the need for a ground based radar unit to be landed with the airborne force. The only previous experience of air insertion of radar units was in the Middle East where an AMES Type 6 radar, otherwise known as a Light Warning Set (LWS), had been modified to be carried in a Hudson or Bombay aircraft and was deployed to 'Marble Arch' in the Western Desert on 18th December 1942 where it became operational only 45 minutes after landing.

Figure 4 -

Wg Cdr Brown

(taken in North

Africa, where

he was a sqn ldr)

The radar equipment selected for the operation was once again the Type 6 radar system. This highly mobile equipment could be housed in a tent or a van sized vehicle. It had a maximum range of 50 miles and was equipped with a range height display and a Plan Position Indicator (PPI) display that meant that it could be used to control fighter aircraft. It had been produced for two main purposes; first, to provide radar cover rapidly in situations where it was not possible to deploy the larger mobile long-range systems and, secondly, to provide low-level forward coverage for larger mobile radar units. Number 60 Group put in place a rapid programme of training and two Light Warning Units (LWU) designated Numbers 6341 and 6080 were formed under the command of Squadron Leaders Wheeler and Coxon respectively. Wing Commander Laurance Brown MBE was appointed as the force commander. Wing Commander Brown was a highly experienced radar officer and controller who had been in the thick of the action during the blitz as a GCI controller and took part in every major amphibious operation in the war including landing on Gold Beach on D day; he was mentioned in despatches three times.

At the beginning of September 1944, Numbers 6080 and 6341 LWUs were transferred from No 60 Group to No 38 Group RAF and attached to Headquarters 1st British Airborne Corps. All in all it was a remarkable achievement to modify the radars and form and train these two units in such a short timescale.

Imagine the chagrin of this force and all who had done so much to prepare it when at a meeting at Bentley Priory on the 15th September the representative of the First Allied Airborne Army stated that the transportable ground radar equipment would not be required for the operation. Wing Commander Brown sought an interview with General Browning on the 16th September at RAF Harwell and the decision was reversed.

The Operation Market Plan

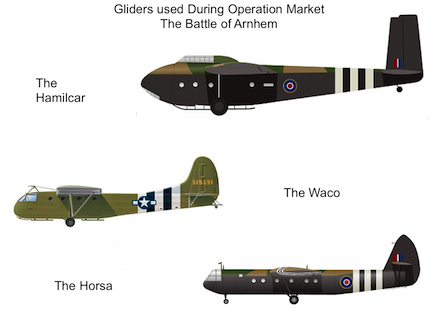

Figure 5 - Gliders Used At Arnhem

The vertical envelopment was to be accomplished in two ways, first, the main assault force was to be inserted via parachute and heavy equipment such as vehicles, artillery and, of course, the LWUs by glider. There were three types of glider, the Hamilcar, Horsa and the American Waco. A lack of sufficient transport aircraft meant that 1st Airborne Division would be dropped in three separate lifts over three successive days. Corps and Divisional headquarters elements, the 1st Parachute Brigade and most of the 1st Air Landing Brigade would land on 17th September. The 4th Parachute Brigade and the rest of 1st Air Landing Brigade would land on 18th September and, on 19th September, the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade would land, along with a supplies for the entire division. It was planned that Wing Commander Brown would go in the first lift on the 17th with the Airborne Corps commander and staff which was scheduled to land at Groesbeek near Nijmegen. Originally it was intended that the LWUs would go on the first lift but a lack of aircraft tugs meant that Numbers 6080 and 6341 LWUs would fly on day two in four Horsa gliders. Each unit was split into two loads which can be broadly categorized as the receiver and display equipment in one load and the transmitter and aerial in the other load; unit personnel were split between their two gliders.

Into Battle

Figure 6 - Stirling

Towing a Horsa

The first lift from Harwell on the 17th went well with 25 gliders assigned to transport the First Airborne Corps headquarters and Wing Commander Brown was on this lift. The picture at Figure 6 actually shows a Stirling towing a Horsa taking off from Harwell on the 17th as part of the Corps HQ lift. Wing Commander Brown could well have been in the glider.

Brown's glider landed safely but he had apparently forgotten his sleeping bag and decided to retrieve it. On his way to do this the DZ was strafed by an Me 109 and Brown was hit. He died of his wounds on the 18th September and is buried in the Groesbeek Canadian War Cemetery. Brown was arguably the most successful interception controller of the war.

Figure 7 - Brown's Grave

As dawn broke on the 18th at RAF Harwell the airfield was covered in thick fog and nothing could move until late morning. Numbers 6080 and 6341 LWUs with a total of five officers including a USAAC 1st Lieutenant from the 9th Army Air Corps and 19 other ranks were to be carried in four Horsha gliders chalk marked 5000 to 5003. With sufficient visibility by 1200 hours the lift started and first combination airborne was chalk 5001 with Staff Sergeant John Kennedy as first pilot and Sergeant 'Wag' Watson as co-pilot. The 'tug' was a Stirling of Number 570 Squadron flown by Flying Officer Spafford RCAF. The formation join up was complicated and Spafford's combination being the first to take off had to fly straight ahead to allow other combinations from Harwell to formate. The Harwell formation then flew to a main rendezvous at which they joined the main attack force. The main formation comprised three streams of aircraft and gliders on the left of the formation and slightly lower flew combinations of Halifaxes towing Horsas, Halifaxes towing Hamilcars and some Dakotas not towing. To the right there were numerous Dakotas towing Wacos some of them actually towing two Waco gliders. In the centre stream in which the LWUs were flying there were Halifaxes towing Hamilcars and Stirlings towing Horsas. It was a truly impressive sight.

The Horsa chalk mark 5000 with Staff Sergeant 'Lofty' Cummins as pilot and Sgt McInnes as co-pilot was carrying personnel and half the equipment of 6080 LWU and took off at 1208 hours; as it approached the turning point at 's-Hertogenbosch for the approach to the LZ the combination experienced heavy Anti-Aircract (Ack Ack) fire. The towing aircraft, which was a Stirling LK121 of 570 Squadron and piloted by Flt Sergeant Culling, was hit. Culling advised Cummins that they would have to slow down but shortly thereafter the Stirling reared up and spun into the ground from 3000 feet killing all on board. Cummins showing great presence of mind managed to cut the towline and landed heavily near the village of Hemmen some seven miles from the LZ and the wrong side of the Neder Rijn river. It was a quiet area and they were quickly surrounded by Dutch patriots all speaking good English who told them they were in German occupied territory. The radar equipment was destroyed by gunfire. The glider pilots and 6080 LWU personnel then headed on foot for Divisional HQ led by a Dutchman on a bicycle. All but Cummins crossed the Rhine by the Friel-Hevesdorp ferry and reached Oosterbeek. Although it is not clear why Cummins tried to cross the Nijmegen Bridge - the glider landed north of the river Waal - he was shot dead by a sniper in attempting to do so.

Loaded into the Horsa chalk number 5001 were personnel from 6341 LWU and half the radar equipment. Known to be on board were Flight Lieutenant Richardson and six other ranks; it is also believed that Squadron Leader Wheeler, OC 6341 LWU, may have been on board although he does not seem to have taken part in the command decisions that followed the landing but he was certainly not aboard the other 6341 LWU glider as will be seen later.

Glider 5001 also experienced heavy ack-ack fire but Staff Sergeant Kennedy was released at the right point and after pulling off to port in a climbing turn made a good approach under machine gun fire and managed to land the glider as briefed running up to the hedge on the LZ.

A dangerous situation had developed to the southern end of LZ-X where a strong German force infiltrated between two of the Border Regiment companies defending the LZ and was able to direct machine gun and other fire at landing gliders.

Figure 8 - Landing and Drop Zones at Arnhem

Horsa glider 5002 piloted by Staff Sergeant 'Teddy' Edwards with Sergeant Ferguson as his co-pilot was carrying personnel and equipment of 6080 LWU and was towed by a Stirling from 295 Squadron. The combination reached the cast off point without damage but during the approach to their designated landing spot 5002 was subjected to the same heavy machine gun fire experienced by 5001 and was set on fire before it landed. Edwards warned everybody on board to disembark as quickly as possible on landing and 'hit the deck'. The only immediate cover on landing was a field of Brussels Sprouts which the men made good use of. Even so, the co-pilot Sergeant Bill 'Fergie' Ferguson was wounded when a bullet travelled the length of his spine opening the flesh but fortunately not seriously damaging the bone. The glider and its load were completely destroyed by fire.

By this time there was still no sign of either Horsas 5000 or 5003 on the LZ both of which were carrying identical loads. By deduction it would appear that both were carrying receiver and display equipment; this assumption is based upon the fact that there is a Type 6 transmitter antenna on display at the Oosterbeek Airborne Museum that most probably came from Horsa 5002. It would appear that Flight Lieutenant Richardson - recorded as the senior RAF officer present - decided that it would be impossible to field a serviceable radar and so he decided to destroy the equipment on Horsa 5001 which was accomplished by Sten gun fire and explosives.

Horsa 5003 piloted by Staff Sergeant Harris with Sergeant Bosley as his co-pilot was being towed by a Stirling from 295 Squadron piloted by Flight Lieutenant Kingdom. The load was most probably the receiver and display equipment for 6341 LWU and there were six personnel from the unit on board. The combination encountered the heavy flak in the 's-Hertogenbosch area that had, as recounted earlier, claimed Stirling LK121 and its entire crew and resulted in Horsa 5000 landing seven miles from of the LZ. Horsa 5003 was hit and it appears that its tail was completely shot away from which there was no hope of recovery. The Stirling managed to cut the tow and the glider crashed one kilometre south of the station at Opheusden along the road to Doodeward – all on board were killed. The senior officer on board was Flight Lieutenant Tisshaw with five other ranks.

Figure 9 - Flt Sgt

Lievense (taken

when he was

an LAC)

With no chance of becoming operational it was now a case of survival. Personnel from both 5001 and 5002, in the company of some airborne troops, made their way to Oosterbeck. However, after coming under fire en route the party became scattered. Lieutenant Davis, a USAAC controller who had probably been on Horsa 5002, 'acquired' a jeep and after collecting as many LWU personnel as possible made a dash for the Divisional HQ which had been set up at the Hartenstien Hotel. He then set them to work digging in behind the hotel; their timing was good because no sooner had they achieved a reasonable level of protection than the Germans launched a very fierce and intense mortar attack. Radios were the Achilles heels of the operation and the LWUs had lost all of theirs. The army radios did not work and during the mortar attack the US air support team's radio jeep, which was on loan to the Division, was damaged. The Americans sought help from the RAF to repair their radios and LAC Roffer Eden, a 31-year-old Wireless Mechanic with 6080 LWU, set about trying to salvage something. Shortly thereafter another mortar salvo rained down and Eden had his jugular vein severed. Despite a valiant attempt by Davis to apply first aid, Eden died later. At about the same time an 88mm round burst about 25 yards away and Flight Sergeant Lievense RCAF, the senior radar engineer with 6080 LWU, was hit three times in the back by shrapnel and he died of his wounds on 22nd September 1944.

Keen to engage the enemy on his own terms, Davis sought permission to lead a patrol of the remaining airmen but this was refused because they were not infantry trained. He then set about getting the men to dig their holes much deeper. This was a very sensible measure considering the ferocity of the mortar bombardment that seemed endless. Corporal Austin who had landed in Horsa 5000 was hit in the head, back and buttocks and was taken to a hospital that was in German hands.

Clearly not one to take no for an answer, Davis, who had infantry training, was allowed to go on patrol and by all accounts he performed very well indeed. However, during a mortar attack he was wounded in the foot and was then restricted to manning a window in the Hartenstein hotel.

Figure 10 -

Sqn Ldr Coxon

Leading Aircraftman Eric Samwells was a twenty one year old radar operator with 6341 LWU and it appears that somehow he went on a patrol from which he did not return.

The Retreat

By the 25th September the defended perimeter around Oosterbeek had shrunk and there were only some 700 yards of frontage on the river in British hands. The order was given for a general retreat and some 2000 men escaped across the Rhine that night. Amongst them were Squadron Leaders Coxon and Wheeler, Flight Lieutenant Richardson and the wounded Lieutenant Davis. Staff Sergeant Edwards, the pilot of Horsa chalk no 5002 and Sergeant Watson, the co-pilot of Horsa chalk no 5001, also escaped. Squadron Leader Coxon is shown in a photograph at Figure 10, which was taken shortly after his escape.

Postscript

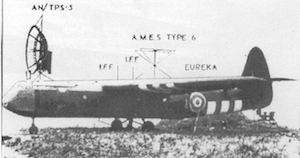

Figure 11 - The Horsa LWU

Although the LWUs never made an operational contribution the lessons learnt were put to good effect. New air transportable systems were devised as follows:

-

Type 6 Mark IX. This LWS was mounted in a four-wheel drive truck with a trailer which carried the communications equipment. It could be carried in a Hamilcar glider and could be brought into action in 30 minutes after landing. Four of these units were produced.

-

Type 6 Mark VIII. This was a light warning set which used an antenna that produced a range not dissimilar to a larger mobile radar unit. It was equipped with GCI cabins for control. It took four Dakota aircraft to deploy it and it could not realistically be brought into action in under 24 hours.

-

Type 65. This was the most novel of the three systems which was known as 'Dinner Wagon'. It comprised an LWS Type 6 and an American AN TPS 3 LWS mounted in a Horsa with a special operations room incorporating additional displays and equipment for linking in landlines and radio telephony equipments. The best-known time achieved to bring this system into action after landing was 8 minutes. Two systems were constructed.

The unit to man and operate these systems was formed under 60 Group and received technical training from this group and number 38 group provided operational training. The unit came under the operational control of the 6th Airborne Division (personnel wore the divisional badge on their shoulder) and was commanded by a Wing Commander with three operational squadrons each comprising four officers and 34 other ranks.

Conclusion

In many of the numerous books on Operation Market Garden including the book written by Major General Urquhart (GOC 1st Airborne Division) no reference is made to the mobile radar force as part of the Order of Battle. Whilst RAF and Army Air Corps history rightly makes much of the truly valiant efforts of those transport, glider tug crews and gliders who delivered troops, supplies and gliders to Arnhem, they makes no similar effort to honour the role of the airmen who landed to perform a vital air surveillance and control role and ultimately had to fight for survival alongside the airborne forces. They paid a very heavy price.

During World War two the Air Ministry actively discouraged the 'Ace' culture. However, the public liked heroes and battles in the air, and the Battle of Britain especially provided a body of such men and the RAF policy became more honoured in the breach than the observance. However, radar and, more importantly, the role of the various RAF radar units was secret and the operational tasks undertaken by personnel from the Control and Reporting (C&R) (now the Aerospace Battle Management) organisation was subsumed within the Signals structure of the RAF. All this, coupled with the passage of time which buries so much, played against the operational achievements and contribution to victory of the C&R organisation being properly recognized and honoured and it also played against officers like Wing Commander Brown being recognized as 'Aces' in their own right. There are so many other controllers, operators, engineers and maintenance personnel who will never be recognised for what they did but bringing a fresh perspective of the achievements of the C&R organisation and rescuing the stories like Arnhem from the outer margins of history will, hopefully, go some way towards redressing matters. The fate of the LWU force personnel that were sent into Arnhem is known and it is summarised below.

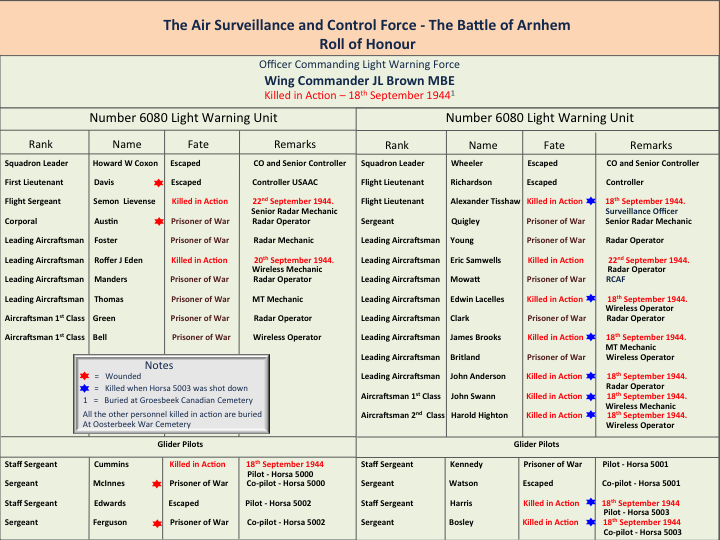

The Roll of Honour