Some (most) elements will not work without it!

Controlling The Lightning

by Kelvin Holmes

Lightnings in the "Q" Shed

During the late 1960s the Lightning was the central element in an air defence system which included ground radars, Bloodhound SAM and tanker aircraft, Victor K1s and K1As. The ground radar system comprised a number of Master Radar Stations (MRS), with both radar and fighter control capabilities, supplemented by various Control and Reporting Posts (CRP) and Reporting Posts (RP), the latter with radars but no control capability. The day-to-day role of this system was policing the UK Air Defence Region (UKADR) based on the Recognised Air Picture (RAP) compiled at the MRSs (each responsible for its own Track Production Area (TPA)) and cross-told internally to other MRSs, to adjacent NADGE/STRIDA sites and passed back to the ADOC at RAF High Wycombe. The fighter Quick Reaction Alert (QRA), Northern and Southern each with two armed interceptors on 10 minutes readiness, was maintained 24 hours a day in case aircraft entering the ADR could not be identified from cross-tell, flight plans or any of the procedural means. Typically each MRS would be associated with a particular fighter airfield which would provide the means to police the air space and, if need be, fight the air battle in its area of responsibility.

The entrance bungalow

to Patrington's R3 Bunker,

photographed in 1983

Such an MRS was RAF Patrington, located near Spurn Head in East Yorkshire, with its associated airfield being the Lightning base at RAF Binbook, home to 5 Squadron. At this time the UK Lightning force was at its peak with the F6s of 11 and 23 Sqns at RAF Leuchars, F3s of 29 and 111 Sqns at Wattisham and 226 OCU at RAF Coltishall. Binbrook shared Southern QRA duties with Wattisham, whilst the Northern QRA was provided by Leuchars. The term Interceptor Alert Force (IAF) was also used for the fighter QRA but from when the author can't recall.

The history of RAF Patrington goes back to WW2 when a Ground Controlled Interception (GCI) station was established in a 'Happidrome' operations block near Bleak House farm cottages. Accommodation was also built on the site. By 1950 'Plan Rotor' envisaged a move into hardened underground bunkers with an R3 at Patrington plus an R2 at nearby Easington for a CHEL site. Ultimately the Patrington site proved unsuitable for a bunker so it was decided to locate the R3 at Holmpton and abandon the R2. RAF Holmpton was completed in 1954 and Patrington GCI closed in 1955. The accommodation site was retained, married quarters added and by 1958 the two site station was re-named RAF Patrington.

Rotor 2 in the mid 1950s introduced the Decca Type 80 'S' band radar which did away with the need for separate GCI and EW radars. Also installed were AN/FPS 6 nodding height finders and the Type 64 PPI radar displays which were used until the site finally closed in 1974. The '1958' Plan - later termed 'Plan Ahead' - saw Patrington re-designated a 'Comprehensive Radar Station' with a local Type 80 Mk 3 supplemented by radar input from Bempton CEW. In 1962 the term Master Radar Station was adopted for the Comprehensive sites, with RAF Patrington, RAF Buchan and RAF Bawdsey nominated as MRSs each with their own sector of east coast operations. For a fascinating and more detailed history of the station and the other MRSs, a visit to www.subbrit.org.uk is recommended.

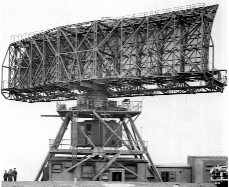

Decca Type 80 Search Radar

As of 1968 then, Patrington was typical of the MRSs of that era being equipped with a Type 80 Search Radar and, if memory serves, three AN/FPS6 height finders supplemented by more modern Type 84, 85 and HF200 radars fed in from the RP at nearby Staxton Wold, but when it came to fighter control the Type 80 was without equal. The Patrington Ops site at Holmpton was buried deep inside an R3 bunker, although the bungalow above with large car park and the radar heads were obvious to all. RRH Staxton Wold is still operational in 2007 (as a CRP in the UK ASACS) and as one of the original 16 radar sites in the Chain Home System back in 1939 is perhaps the oldest operational radar station in the world.

Type 84 Search Radar

(Photo: ADRM Neatishead)

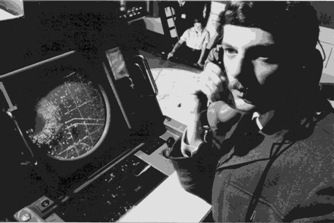

Training as a Fighter Controller began at MRS Bawdsey where an intensive 10 week interception controller's (IC) course included live sorties with the Meteors of 85 Sqn and simulator work using a system produced by the Mullard Company and always referred to as the "Mullards". Mullards gave controllable radar contacts on the screen with airmen/women driving the contacts and providing R/T as if from a pilot. During the course a U/T controller would complete perhaps 60 live and 250 'synthetic' (as the log book records) runs learning the geometry of interceptions, how to assess target speed & heading and then determine the vector to intercept. Mullard training would include subsonic and supersonic practise interceptions (PIs), with both aircraft under control, plus QRA profiles with an unknown target and the fighter only under control. The tools of the trade, probably still in use today, were a chinagraph pencil and an overlay, the latter being a clear plastic sheet maybe 4 inches square marked out with angles and ranges. RT procedures were all important such that a call prefixed with 'port' would initiate a fighter turn in that direction whilst 'left' was information. Completion of the Bawdsey course brought a posting to a MRS where training continued for a further four months, including Display Controller (DC), Fighter Marshal and IC duties. The DC was responsible for the MRS air picture and for liaison with the adjacent NADGE/STRIDA site, in the case of Patrington, the Danish station Karup. A visit to Karup was essential as part of DC training. For the IC it was more Mullards and, under supervision, control of Victor tankers, Lightnings and Phantoms. Typically some 140 live interceptions, supplemented by a similar number of Mullard runs, would qualify a controller to go solo by which time he, or she, would be familiar with the local operating environment, danger areas, airfields and recovery points.

Ready for Split

(F3s of 74 Sqn)

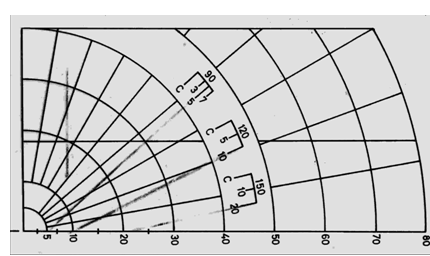

Control of the Lightning was built around various standard approach paths to the target, these being identified by the number of degrees - 90, 120, 150, 180 - through which the fighter would turn to roll out behind the target on the same heading at a range of about 2 miles. For a '90' against a subsonic target, for example, the controller would aim to have the fighter approach the target on the appropriate heading (e.g. target heading 240, fighter closing from the South on 330) such that the target eventually crossed the fighter's nose at range 5 nautical miles (nm). At this point the turn onto target's heading would be ordered - 'port 240'. An AI radar or even visual contact should be assured at this range with the final 90 degree turn keeping the target in view and bringing the fighter in behind for a missile or guns attack, or for a VISIDENT. By practising these profiles the IC would become proficient in assessing headings and turn points and the fighter pilot with the presentation (ranges and angles-off) on his AI scope. Types of control included close and loose, with the IC providing anything from full target data and interception control (Alpha control) to just target ranges (Delta control) where the pilot was required to interpret the AI and calculate his own interception geometry. In all cases the IC was waiting for the 'Judy' call indicating that the fighter was now able to complete the interception with no further help. On occasion the 'Judy' call could be followed by a request for 'More Help' so the controller had to keep alert. The introduction of Red Top saw a new interception profile against supersonic targets - the frontal attack. For this the controller would place the fighter on a 150 collision flying straight through the target's track with the possibility of a 150 turn if a stern re-attack became necessary. Another unusual profile, the 'fast 525' , was that needed to intercept and identify a very high flying subsonic target. This required a 180 flown at supersonic speed turning in behind and still well below the target; having rolled out behind speed would be traded for height with the fighter climbing up behind the target to make the VISIDENT before dropping back to lower level. The timing of the 180 turn was crucial - too late and the climb would place the fighter too far behind the target to identify it, too soon and you could end up in front. At the heights involved there was no second chance.

Visident of a Bear

(Photo MoD)

At MRS Patrington, normal day-to-day manning included a Chief Controller (Air), normally a Flight Lieutenant, and the ICs who were mainly Pilot Officers, Flying Officers, Flight Sergeants and Warrant Officers. Most ICs were career Fighter Controllers although a fair proportion were aircrew either on ground tours or who had transferred to FC on completion of their flying duties. Patrington comprised a main ops room with the sunken well containing the plotting table with projected radar picture (the PDU) and smaller rooms (cabins) each with three IC radar consoles. These consoles, as with all others throughout the MRS, displayed raw radar from whichever head had been selected by the operator. Various range scales were available with 160 and 240 miles being the most commonly used. Superimposed on the radar was an outline map showing the coastline and lines of lat/long as Georef. The Georef 'squares' most used by Patrington for Lightning control were AK, BK, CK, AJ, BJ and CJ, giving an area 120 by 108 nm. All supersonic runs had be completed 30 nm from the coast to avoid upsetting the locals.

Adjacent to the main ops room, where the CC(A), CC(SAM), DC and plotting team of Air Defence Operators (ADO) were situated, were the Fighter Marshal (FM) position and the Height Finder console room, the latter manned by SACs. The FM provided the link between the local Air Traffic Control Radar Unit (Northern Radar at RAF Lindholme for Patrington) and the interception team, controller and assistant. For low level sorties the IC would speak direct to Binbrook approach but usually Northern were used. The main tote in the Ops Room - perspex and for the ADOs a chance to stand behind and demonstrate the backwards writing skills - was used to show the flying programme: airfield, callsigns, aircraft type, planned take-off time, mission type and operating area.

CC(A)'s position in the Patrington Ops room,

with the Plotting table visible below

So, sitting in the crew room, a call from the CC(A) over the squawk box would despatch the IC to a console "a pair of Mk 6s from Binbrook, S7A, area AK and BK, oh and the're already airborne". Down to the cabin and the console has been set up by the supervisor, and the assistant, courtesy of the FM, has Northern on the line "two Lightnings C11 and C12 in AJ 2055, FL250, ready for handover"; good old Type 80, there they are on the screen "OK, radar contact, tell them to call Patrington on Fighter Stud 51". A few moments later the R/T would crackle into life "12, 11 check", "11 loud and clear", "12 loud and clear, Patrington this C11 and 12", "11, loud and clear, radar contact", "11 Roger, 11 on the left, fighter 1st run, ready for split". "11, port 020, 12 starboard 150, over"; "11 Roger, port 020", "12 Roger, starboard 150" and the split was underway. The aim here for a typical subsonic run, with target at .85M and fighter at .95M, was to split the two aircraft by about 30 miles after which they would be ordered back towards each other in the required geometric profile.

A typical Overlay

For full close control - say, for a 90 - the IC needed to get the fighter on the right heading with the target 35 degrees off the nose at 30 miles range. By 20 miles the angle would reduce to just over 30 degrees and by 10 just over 20; these relative positions were all clearly marked by a Line of Position (LOP) on the overlay and would lead to "dead ahead 5 miles" and an instruction to turn onto the target's heading. With the final turn underway 'Judy' would be called, followed by "Splash, ready for split" and the next run would commence with fighter and target swapping roles and the controller providing range and bearing to Binbrook's recovery point "11, 12, Pigeons to Point Alpha 240, 40 miles" and an update on base weather "base is blue" was good with the report "Black 3" (indicating crosswinds) most unwelcome. The controller would have several overlays to hand marked with the LOPs for different profiles - certainly the standard 90, 120, 150 and 180. A typical subsonic Lightning sortie would comprise three or four PIs with, for the last run, the target heading back towards Point Alpha from which, on a heading of 210, the aircraft would arrive overhead base in about 2½ minutes. Recovery was normally through Northern, with a constant battle between the pilots, who wanted to squeeze as many PIs as possible from each sortie, and the Air Trafficers, who wanted the handover to take place at least 30 miles NE of Point Alpha.

Patrington Control Cabin 3 (IC 9) with the

Firebrigade displays above the comms console

Running through Patrington's main operating area were the Blue 1 and Upper Blue 13 airways leading to the bane of most sorties - transiting airliners. It was, and presumably still is, the fighter's responsibility to keep clear and the reporting of "strangers" by the controller occurred throughout most sorties. The problem was far worse to the south for OCU aircraft out of Coltishall or the F3s from Wattisham. Up north at MRS Buchan, controlling the Leuchars-based F6s, strangers were more of a rarity. A Fighter Controller's comparison of his duties with the Air Trafficer's would invariably suggest that whereas they just keep them apart, we join them up and keep 'em apart; much more skilful!!

In the Patrington area QRA activity was scant with most trade occurring further north. A few Bears were known to penetrate as far south as 54º North, by which time they had been thoroughly intercepted, identified and shadowed all the way from CRP Saxa Vord and points north. On occasion, the QRA would be scrambled for missile firing and this would be initiated by a call from ADOC.

Victor tanker and Lighting F6

Meanwhile, the MRS QRA watch-keeping continued - for each watch it was 2 days on, 1 day off, 2 days on, 3 days off. The 2 days on comprised 0830 - 1200 and 1700 - 2300 on the first day and 1200 - 1700 and 2300 - 0830 on the second. The team was a CC(QRA), an IC, a DC and about 10 airmen/women who formed the plotting team and controllers' assistants. Perhaps the most unwelcome event during a midnight shift was a call from the guardroom upstairs saying that a Taceval team was on the way down, or getting your head down in the Wing Commander's office and being left there when everybody else went off watch at 0830 - "good morning Sir, I was just....".

So, whereas PIs were the day-to-day business, Air Defence exercises and Tacevals would provide a real test of the controller's and Lightning pilot's skills. Here the entire MRS would be manned from Master Controller (MC) down, with the Telebrief Scrambler (TS) providing a running commentary on the air situation to Wing Ops at Binbrook and the waiting aircrew. In truth, only a few words would truly grab their attention, "Scramble" being most likely to provoke a reaction. Working in conjunction with the Control Executive (Conex), it was the MC's responsibility to order fighter readiness states, establish Tanker towlines, assign fighters to raids, and to pass scramble orders to the TS, another role performed by an IC qualified person. The exchange between TS and Wing Ops always followed a set format: "Binbrook, alert 2 (or however many) Lightnings" would elicit from Wing Ops the mission numbers, say "23, 24"; then "23, 24, Vector 060, Flight Level 240, call Patrington Fighter Stud 54, Scramble, Scramble, Scramble". An IC would also scramble to a radar console, where a briefing from the CC(A) would give mission details including task 'intercept and identify', 'shadow' or 'destroy'. With the 'threat' predominantly from the east or north east most interceptions were based on the 180 with fighter and target on reciprocal courses, displaced by 10 miles, to be achieved by target range 30 miles, although, this time, tactics rather than the geometry of PIs were the aim. The first factor was target speed followed closely by, if known, target height; should the target be supersonic further options opened up dependent on whether the fighter was Red Top or Firestreak fitted. For stern attacks the displacement ideally would place the sun behind the fighter on the final turn in behind the target and the run in would be flown at a 'no trail' height. Target height-finding was always a problem; the controller would mark the target radar response with the inter console marker and press the 'request height' switch - this would send a request to the HF operator where, if free, an HF radar would be swung round to the target's bearing and the nodding commence. If a target was found at the right range this would be marked and the height passed back to the IC's display. With a limited number of HF radars and many ICs active, requests were often queued and even when the head became available 'No Height found' was always a possibility. The best data was provided by a 'Relative Height' request where the IC would mark both fighter and target and the HF would return just that. A call to the fighter "target 15 left, range 20, 6000 above" would enable the pilot, heads down in his tiny radar display (smaller than an overlay!) to refine the scanning pattern and steer his antenna to optimise the chances of acquiring the target. A majority of interceptions were completed with no height information at all, giving the pilot even more to do. No doubt today with 3D search radars and improved AIs these problems are less severe. With the Phantoms out of Coningsby, the 'Judy' call came at very long range, giving the controller little to do but keep an eye on those strangers. Ask any controller though and most will say they prefer Lightnings. The limitations of the AI23B meant that the controller had a real contribution to the mission and with evading targets and poor geometry the aircraft had the power and manoeuvrability to reach a Judy position.

IWI Course,

circa October 1972

(author 2nd from right)

Even in those days, the use of computers to control interceptions was envisaged and at Patrington one of the cabins was fitted with the huge displays, rumour had it ex-British Rail, to display information from the Firebrigade system. This required initialisation with winds aloft data and careful manual tracking of both fighter and target by IC1; IC2 would be on the R/T reading out the vector instructions to the fighter and watching for strangers. Each interception progressed through a sequential multi-leg profile and on occasion the system would send the fighter away from the target to gain the range needed to perform the text book acceleration to attack speed. The system seemed to take the efforts of two ICs to achieve a single interception whereas on a good day a single IC could control 2 or even 3 simultaneous interceptions using the overlay. Still lessons were learnt about how best to use computer assistance for interception work and it probably still goes on today.

Some controllers were fortunate enough to attend the Intercept Weapons Instructor (IWI) course at the Lightning OCU RAF Coltishall, with control undertaken from nearby RAF Neatishead; the R3 at this MRS was destroyed by fire in 1966 but limited control facilities were available in an above-ground ops room. The IWI course included sandbagging - air familiarisation trips in a T4 or T5 where the controller would hear what it was like to be controlled and start to get an understanding of the tasks involved in operating the Lightning. Successful completion of the four month course resulted in the award of a certificate and the right to be known as IWI (GE), the GE standing for Ground Environment. Another significant event in the life of all controllers was the annual visit by the Control & Reporting Evaluation Team (later re-named the Air Defence GE Examining Board - ADGEEB) or as they were affectionately known 'the trappers'. A visit by the trappers meant examination of your skills and knowledge as a controller; a posting to the trappers gave the opportunity to visit all the FC units but the potential to lose your friends in the process.

With Lightnings deployed in Cyprus (56 Squadron at Akrotiri), Singapore (74 Squadron at Tengah) and Germany (19 and 92 Squadrons), the late 60s/early 70s gave many opportunities for overseas postings for Fighter Controllers. In Cyprus, a detachment to Mount Olympus (Troodos) afforded a temporary relief from the heat of Cape Gata whilst, in Singapore, a trip to Western Hill near Penang made a change from Bukit Gombak just off the Bukit Timah Road. There was even a Type 80 in Malta with occasional fighter deployments to RAF Luqa. Other postings such as Aden and - later - 3 Air Control Centre (ACC) at Hamala Camp, Bahrein, were perhaps less sought after. 3ACC, which closed in 1971, used Type 88 and 89 static radars to control 8 & 208 Sqn Hunter FGA9s from Muharraq and also had an AN-UPS1 mobile radar; the 'Upsi' was routinely deployed to Masirah when tankers and fighters were transiting between the UK and Singapore.

AEW Shackleton

Western Hill was responsible for the control of fighters, mainly RAAF Mirage IIIs, based at nearby RAAF Butterworth and was equipped with a GL 161 transportable system, with the AN-TPS34 radar, and in RAF service was known as "Tinsmith". A second Tinsmith system formed the basis of No. 1 ACC which, when not deployed, was based at RAF Wattisham in Suffolk. Collocated with 1 ACC was the Tinsmith Software Support Unit (TSSU) which, in the mid 1970s, was responsible for development of the interception aid software (IAS) which attempted to "automate the overlay".

The air defence system was given a significant boost in January 1972 by the introduction into service of the AEW Shackleton. The Shack provided fighter control and voice tell of tracks detected on its aging AN-APS20 radar, previously fitted on the RN's Gannets. Tracks told in would be shown via plaques on the MRS plotting table. A posting to 8 Squadron at Lossiemouth gave a fighter controller the right to wear an aircrew brevet as today on the E3.

Ex-Binbrook Lightning F6,

preserved at Bruntingthorpe

(2004 photo)

By the early 1970s Patrington had become a Sector Operations Centre/Control & Reporting Centre (SOC/CRC). With the introduction of the Linesman System based on an Air Defence Data Centre at RAF West Drayton and the refurbished R3 sites at Neatishead and Boulmer serving in a Standby Local Early Warning & Control (SLEWC) role, Patrington closed in 1974. Linesman itself was a flawed concept and West Drayton has since closed with the UKADGE system, based on most of the old radar stations, taking its place. Control of Lightnings in the final decade was carried out primarily from the two former SLEWCs with the School of Fighter Control moving from Bawdsey, via West Drayton, to RAF Boulmer. The control of Tornado F3 and, more recently, the Typhoon no doubt requires different procedures to the Lightning so the days of close control are probably long gone. As of 2007 both the Patrington Happidrome GCI building and Holmpton R3 are still in existence; the former is derelict but the R3 is used by Defence Archives and is open to visitors.

There are plenty of Lightnings preserved in Museums but if you want to see one moving in the UK a visit to the Lightning Preservation Group (www.lightnings.org.uk) at Bruntingthorpe is the only place. Lastly the Air Defence Radar Museum (www.radarmuseum.co.uk) at Neatishead is a must.